Nurse Pronto is free for only 2 more weeks!

Everyone Thinks I’m a Nurse… I’m Not Sure I Believe Them Yet

Many nursing students worry they will not be good nurses, even while excelling in class and clinicals. This blog unpacks the hidden psychology of imposter syndrome in nursing education, using real data and real experiences to explain why self-doubt is so common and why it does not mean you are failing. Written for students who care deeply and feel the weight of responsibility, this piece reframes fear as part of becoming a safe, thoughtful nurse.

12/23/20256 min read

“Everyone Thinks I’m a Nurse… I’m Not Sure I Believe Them Yet”

Imposter Syndrome and the Quiet Fear of Becoming a Bad Nurse

There is a moment in nursing school that almost every student reaches, usually late at night, usually after clinicals, and usually alone. It is the moment when the noise finally settles and a thought slips in that feels dangerous to say out loud. I don’t think I’m going to be a good nurse. Not because you do not care. Not because you are failing. But because the responsibility has started to feel real, and your confidence has not caught up to the weight of it yet. That thought does not arrive with drama. It arrives quietly, dressed up as realism, sounding suspiciously like insight.

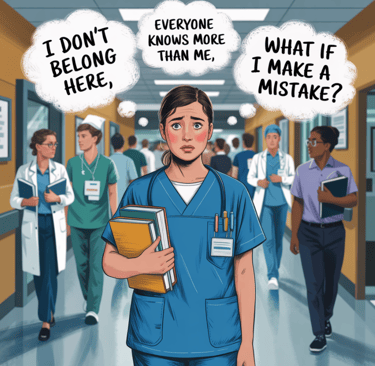

Imposter syndrome in nursing students does not look like arrogance or self pity. It looks like dedication that has nowhere to land yet. It looks like overpreparing, second guessing, replaying clinical moments long after you get home, and dismissing praise the moment it is offered. It looks like students who pass exams, show up early, care deeply about patient safety, and still feel like they are somehow tricking everyone around them into believing they belong. The internal narrative is not “I am better than everyone.” It is “I am one mistake away from being exposed.”

Research suggests this experience is far more common than most students realize. Multiple studies across nursing programs internationally have found that a majority of nursing students report moderate to high levels of imposter phenomenon, with some studies placing prevalence well over 60 percent and others nearing 80 percent in final year cohorts. In other words, feeling like a fraud while learning how to care for human beings is not an outlier experience. It is the norm. And yet, because it is rarely talked about openly, each student assumes they are the only one silently struggling with it.

Part of the reason imposter syndrome takes such a strong hold in nursing school is because nursing education is not just skill acquisition. It is identity formation under pressure. You are not only learning how to calculate dosages, interpret labs, or chart accurately. You are learning how to carry authority, responsibility, and trust while still feeling unsure of yourself. You are asked to step into rooms where people are vulnerable, frightened, or in pain, and you are expected to contribute to their care while your own confidence is still under construction. That mismatch creates fertile ground for self doubt.

Clinical environments intensify this experience. Students are observed constantly, corrected publicly, evaluated formally, and compared silently. Every movement feels visible. Every pause feels suspicious. Even neutral feedback can feel like an indictment when you are already questioning your competence. Studies examining stress among nursing students consistently identify fear of making mistakes and fear of harming patients as two of the most significant contributors to anxiety during training. More than half of nursing students report that concern about patient safety keeps them in a near constant state of vigilance during clinical practice. That fear does not make someone weak. It makes them human in a system that carries real consequences.

What often goes unspoken is how that fear gets translated internally. Instead of interpreting anxiety as a normal response to responsibility, many students interpret it as evidence they are not cut out for nursing. Instead of recognizing uncertainty as part of learning, they read it as personal deficiency. The brain, uncomfortable with ambiguity, looks for a story that explains the discomfort. Unfortunately, the story it often chooses is identity based. I’m not a real nurse. I don’t belong here. Everyone else has it figured out except me.

Comparison plays a powerful role in sustaining that story. Nursing students are surrounded by peers who appear confident, capable, and composed, at least on the surface. What is less visible is that many of those same peers are privately reporting high anxiety, self doubt, and fear of inadequacy. Research on confidence and anxiety in nursing students shows a near even split, with roughly half reporting strong self confidence and nearly the same proportion reporting significant anxiety at the same time. These states are not mutually exclusive. Someone can appear confident and still be deeply uncertain. Someone can perform well and still feel unworthy of the role.

Imposter syndrome also thrives in silence because nursing culture has historically rewarded composure and penalized visible uncertainty. Students quickly learn that asking questions can feel risky, that admitting confusion can feel like failure, and that confidence is often interpreted as competence even when it is not. This creates a hidden curriculum where students believe they must feel ready before they act, even though readiness in healthcare is built through action, not discovered through feeling. The result is a generation of students who are clinically cautious but emotionally harsh with themselves.

It is also important to acknowledge that imposter syndrome does not exist in a vacuum. For some students, these feelings are compounded by systemic factors such as being first generation in healthcare, experiencing bias, or entering environments where they do not see themselves reflected in positions of authority. In those contexts, feeling like an outsider may not be an irrational fear but a learned response to subtle messages about belonging. Critics of the imposter syndrome framework have pointed out that framing these experiences purely as individual pathology can obscure the role of institutional culture in creating them. Sometimes the problem is not that the student feels like a fraud. It is that the system has not made space for them to feel secure.

When nursing students say they are afraid they will not be good nurses, what they are often expressing is not incompetence but ethical seriousness. The fear of harming a patient reflects a deep understanding of the stakes involved in care. It reflects respect for the role and an awareness of its power. Ironically, the students who worry the most are often the ones who will become the most careful, reflective practitioners once experience tempers fear into judgment. Clinical competence does not emerge from confidence alone. It emerges from repetition, feedback, and the ability to learn from uncertainty rather than be paralyzed by it.

One of the most important shifts nursing students can make is separating confidence from competence. Confidence is a feeling. It fluctuates. Competence is behavior. It can be practiced, measured, and improved. You do not need to feel calm to follow protocol. You do not need to feel certain to ask for clarification. You do not need to feel like a nurse to practice nursing behaviors safely. Waiting to feel confident before acting often delays the very experiences that build confidence in the first place.

Another critical reframe involves recognizing that being new is not a flaw. It is a developmental stage with its own responsibilities. New practitioners are expected to ask questions, double check their work, and rely on systems designed to prevent errors. These behaviors are not signs of weakness. They are hallmarks of safe practice. The danger arises not from uncertainty but from pretending uncertainty does not exist. Nursing students who acknowledge what they do not know are engaging in risk reduction, not self sabotage.

Practically speaking, students struggling with imposter syndrome benefit from grounding their self assessment in evidence rather than emotion. Keeping a brief reflective log after clinicals that captures specific actions, decisions, and learning moments can help shift the focus from identity to process. Instead of asking, “Am I a good nurse,” the more useful question becomes, “What did I do today that reflected safe practice, and what am I actively learning?” Over time, these concrete markers build a narrative of growth that is harder for the imposter voice to dismiss.

Language also matters more than students often realize. The phrases we repeat internally shape how the nervous system interprets experience. “I got lucky” undermines preparation. “They were just being nice” erases observed competence. “I’m bad at this” freezes development. Replacing these scripts with language that reflects learning rather than judgment does not mean lying to yourself. It means describing reality more accurately. Learning is not linear, and competence is cumulative.

For educators and preceptors, there is a parallel responsibility. How feedback is delivered, how mistakes are framed, and how questions are received all influence whether students internalize learning as growth or as evidence of inadequacy. Students do not only learn skills from instructors. They learn how to interpret themselves. Environments that normalize uncertainty as part of safe practice produce clinicians who are more likely to speak up, ask for help, and prevent errors. Environments that equate confidence with worth tend to produce silence, not safety.

Ultimately, the belief that “I won’t be a good nurse” is rarely a prediction. It is a snapshot of someone standing in the middle of becoming. Most experienced nurses can look back and identify a time when they felt exactly this way, even if they no longer talk about it. What changed was not their personality or their intelligence. What changed was exposure, repetition, and the gradual realization that competence grows quietly, often without the emotional fanfare students expect.

If you are a nursing student carrying this fear, it is worth saying this clearly. Caring deeply does not disqualify you. Doubting yourself does not mean you are unsafe. Feeling unsure does not mean you are failing. It means you are learning to hold responsibility before it feels comfortable. Over time, with practice and support, that discomfort becomes familiarity, and familiarity becomes confidence. Not because you became perfect, but because you became practiced.

Most good nurses were once students who were afraid they would not be good nurses. They kept going anyway. They learned how to function alongside fear instead of waiting for it to disappear. And eventually, without realizing exactly when it happened, they stopped feeling like imposters and started feeling like professionals.

Not because the doubt vanished entirely, but because it stopped being in charge.